Gijsbert Stoet, University of Glasgow

Many of the world’s leading economies can do more to help struggling teenagers to get a better level of education that will equip them for later life. A new report from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), looking at why low-performing students fall behind at school, has found that much remains to be done to reduce the number of children that perform poorly in maths, reading and science skills.

One of the most striking aspects of the report is just how many children are low performers, even in highly-developed nations such as the UK, Australia, or the US. I find it shocking that one in six children in the UK has a low level of reading comprehension skills – 17% of those tested in both the UK and US, and 14% in Australia.

The new report is based on data taken from the OECD-funded Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), the world’s largest and most influential educational survey. It aims to raise educational standards by providing detailed information about successful and less successful educational systems.

Every three years, 15-year-old children around the world take the two-hour PISA test. It focuses on some of the most fundamental academic skills: reading comprehension, mathematics, and science literacy. The new report is based on the 2012 PISA round, in which nearly half a million children participated.

The average score in OECD countries for each skill is around 500 PISA points. For example, in the UK, children’s scores in reading comprehension ranged from 121 to 788 points, with a national average of 499 points. Low performance is defined as a score below (approximately) 400 PISA points. According to the OECD, a low performer does not have the skills required to participate fully in a modern society.

The numbers of low performers in mathematics are worse than in reading – 22% in the UK, 20% in Australia and 26% in the US. Of course, it is possible that a child is a low performer in only one of the skills, but the numbers of children performing poorly in all of the three skills is still worryingly high: 11% in the UK, 9% in Australia, 12% in the US and 13% in France.

Which countries do best

There are considerable differences between countries. Those that generally score highly in PISA are, unsurprisingly, also the countries with the fewest low performers. Generally, East Asian countries and economic regions are successful in PISA (with the Chinese cities Shanghai and Hong Kong leading the league table) and have relatively few low performers. But there are European countries that have a similar level of success. For example, Estonia has one of the highest PISA scores in Europe, and only 3% of children are low performers in all three skills, leading the European league table.

There are no simple explanations for why some countries do better than others – many factors play a role. These include the educational levels and income of parents, their engagement, and whether or not children live in an urban or rural area. We should not only look at the leaders of the league table, but also at countries which are culturally and geographically similar.

Take Ireland, for example, which has 10% low performers in reading and 17% in mathematics and has seen a considerable reduction in low performers between 2006 and 2012. In Ireland, only 7% of low-performing children skipped school at least once in the two weeks before the PISA test, compared to 27% in the UK and 45% in Australia. Ireland’s data also shows a lower level of segregation by educational achievement. Such comparisons suggest that dealing more effectively with truancy and a more equal distribution of low performers across schools might help to drive down the numbers of low performers in other countries.

Gender gaps persist

This new OECD report also reports gender differences among low-performers. From other research, we already know that boys fall behind in education around the world, and in the UK in A-Level and GCSE exams. In particular, boys fall behind in reading, and girls, to a lesser extent, in mathematics.

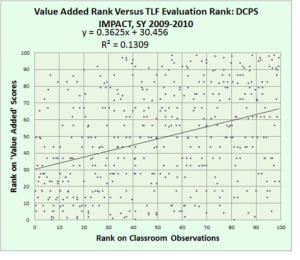

Gender gaps at age 15.

OECD, PISA 2012 Database

These gender gaps are also reflected in the new report. As the graph above shows, more boys than girls are low performers in reading and science, whereas more girls are low performers in mathematics. Policies aimed at reducing gender inequalities have so far not been effective in resolving these gaps. A new approach is needed.

One of the problems that the report does not address is that countries with a larger mathematics gap often have a smaller reading gap and vice versa. This is enormously challenging, because some of the countries, such as Iceland or Finland, that are able to eliminate the mathematics gap affecting girls, have a particularly large reading gap affecting boys.

How to raise achievement

The final chapter of the report lays out a series of policies to tackle low performance levels. It gives examples of successful approaches, which include language training for non-native speakers and improving the quality of pre-primary education, which has happened in Germany. It also suggests that schools could foster high academic expectations, and use networks of schools to disseminate best practise.

It concludes that the percentage of low performers in any country can be reduced within a couple of years, if government is willing to reform the education system. While the number of low-performing children in the OECD is disappointingly high, with the appropriate educational reforms, based on evidence, a lot can be done to improve the situation.![]()

Click here to read all our posts concerning the Achievement Gap.

Gijsbert Stoet, Reader in Psychology, University of Glasgow

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.